Unfortunately I tweeted this five years ago and it’s still true. Unfortunately I tweeted this five years ago and it’s still true. Introduction I have enjoyed my MD/PhD training and am excited for my future career. But in some sense, I think I got lucky: there are good reasons to do an MD/PhD, and bad reasons to do an MD/PhD, and I decided to do an MD/PhD for both good and bad reasons. In this blog post, I review some of those reasons—as well as others that I think are common—in the hopes that your decision-making process about whether to do an MD/PhD will be better than mine. Context Prior to starting college, my plan was to eventually work internationally as a wildlife vet. During college, I read books by Paul Farmer, studied and interned in middle-income countries, and learned about GiveWell. These things convinced me that I could potentially do a lot of good by pursuing a career in global health, and I switched from being pre-vet to pre-med. However, I was always more academically drawn to the humanities and social sciences, so I pursued an independent concentration in human rights (which was ~80% political theory classes, plus a bit of anthropology, sociology, history, and philosophy). I decided to do an MD/PhD in the social sciences because: (1) it seemed like a good way to reconcile my diverse academic interests, (2) I was drawn to a career that would allow me to both help people directly (via medicine) while also addressing structural issues (via my research), (3) some people I really admired (and whose careers seemed amazing) had done MD/PhDs in the social sciences, (4) it seemed like a powerful degree combination that would allow me to do a lot of good, and (5) I wasn’t sure what exactly I wanted to do, and earning a combined degree seemed like it would leave open many career paths. Even now, all of those reasons intuitively seem reasonable to me, but when subjected to closer scrutiny, some start to seem less compelling. There were also other reasons floating around in the background, which I’ll get into. Six bad reasons Reason #1: It’s free Elaboration: If you do an MD/PhD, you will generally not pay for medical school, and will typically earn a ~$40k stipend for eight years; by contrast, the median medical student will accrue $215k of medical school debt. So just to do some simple math, you will earn about $320,000 ($40k/year * eight years) as an MD/PhD student, whereas if you were to only earn an MD, you would lose about $215k. You might therefore think that the financial value of the degree to you is at least $320,000, and possibly more like $535,000 (if you otherwise would have just done an MD, although this number is overstated, since many MDs don’t repay all of their medical school debt due to programs like public service loan forgiveness). Why I don’t endorse this reason: How financially advantageous it is to get an MD/PhD will depend on what your counterfactual is; if you’re comparing doing an eight-year MD/PhD to doing an eight-year English literature PhD, I would agree that the economic value of the MD/PhD is higher. But when compared to just doing an MD (which seems to be the most common alternative for people who are considering applying to an MD/PhD), you will lose (on average) four years of an attending’s salary. How much this is will depend a lot on your specialty, where you practice, and so on, but the average attending physician earns around $350k per year. This means that the amount you could expect to make in four years as an attending is in the ballpark of $1.4 million—i.e., a lot more than $535,000. (Of course, this is a simple calculus: if you are the kind of person who wants to do an MD/PhD, you are probably not super much in it for the money. My argument is just: “this seems like a financially good deal” is not a good reason to do an MD/PhD, because it likely isn’t.) Reason #2: You want to prove something to others Elaboration: My pre-med advisor told me that I probably wouldn’t get into medical school unless I took more biology classes. I was pretty sure he was wrong, and him asserting this lit a fire under me to prove that. This story is one I have heard from others, too—maybe it wasn’t your pre-med advisor, but instead your parents, or an unsupportive teacher, or a society that didn’t believe in you, and you want to prove them wrong. Why I (basically) don’t endorse this reason: Proving people wrong is one of life’s great joys. I am especially sympathetic to wanting to do this if people systematically underestimate you. But it’s worth interrogating this reason closely. First, proving people wrong—like posting about how you got into an MD/PhD program on social media—tends to only provide fleeting satisfaction. “I showed you!” likely isn’t going to provide sustained motivation or happiness throughout the ~2,500- to 3,500-day grind of doing an MD/PhD. Second, there are often multiple ways to prove people wrong—you can do great things (and show people they underestimated you) via multiple paths, not just by doing an MD/PhD. Finally, while it is true that random people you encounter will be impressed when you tell them you are getting an MD/PhD, their opinions usually don’t matter much; the people who will shape your career will evaluate you primarily based on the quality of your work, not on whether you have an MD/PhD (in part because you will likely apply to positions other people with MD/PhDs or similar academic credentials will apply to. I think it can also be the case that doing an MD/PhD sets evaluators’ expectations higher—like: “You had several years to do research and publish stuff—what do you have to show for yourself?”) Reason #3: You want to prove something to yourself Elaboration: Part of the reason I wanted to do an MD/PhD was to prove to myself that I was really academically capable (something I was insecure about because I had academically underachieved in high school, and then been admitted from the waitlist to my college class). Why I don’t endorse this reason: First, degrees are not going to give you good self-esteem. It can seem this way from interacting with arrogant people who have fancy degrees, but I suspect most of these people were either arrogant to start with or are actually insecure, and this manifests as them touting their achievements. Second, many things about medical school and graduate school will probably make you feel bad about yourself; for instance, being around people who are smarter than you, not getting enough feedback (or getting mediocre feedback), the lack of clear standards and expectations, taking exams that you won’t always perform well on, and experiencing lots of rejection (e.g., from journals). In short, while it intuitively seems like doing things smart people do would make you feel smart, it often doesn’t work this way. If you want to feel intellectually better about yourself, I would recommend: (1) aging, (2) surrounding yourself with supportive people, (3) cultivating other values, and (4) defining and pursuing intellectual projects that you enjoy, independent of whether other people are impressed by them (e.g., writing blog posts, learning a language, or reading books). These things won’t always make you feel more intellectually capable, but can help you realize you’re intellectually capable in the ways you care about, while also helping you recognize that there are (many) things more important than being smart. Reason #4: Doing an MD/PhD will allow you to keep your career options open Elaboration: Part of the reason I wanted to do an MD/PhD was because I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to do academic medicine, work (potentially internationally) on global health issues, or focus on health policy domestically. Doing an MD/PhD seemed like a good way to preserve all of these options. Why I don’t endorse this reason: First, doing an MD/PhD to keep career paths open is like buying a chocolate bar for $1,000; no one is disputing that chocolate is good, but you just shouldn’t spend that much on it. Similarly, I think there is a lot to be said for making some sacrifices to keep your options open. Many of us are taught from an early age to do this—by, for instance, working hard in school. But the time and opportunity cost of doing an MD/PhD is just way too high to justify doing one for this reason, given you will spend at least 20 percent of your career just earning your degrees (eight out of about 40 years, and this doesn’t account for residency training, or the fact that you will be working especially hard during those years). Given the time investment involved, it doesn’t make sense to do an MD/PhD to achieve some vague, poorly-defined end. Second, the “keeps options open” thing is a bit of an illusion, since doing an MD/PhD forces you to forgo career flexibility during your 20s—a crucial period of career exploration for most people, since many do not yet have kids, a long-term partner, elderly parents, and so on, and are therefore more mobile and have fewer financial and other obligations. During my MD/PhD, I have had to pass on applying to multiple jobs that I would’ve otherwise been very interested in. None of these specific opportunities will be available to me when I complete my training because they’ll have hired other people. (That said, it’s not like you can’t explore at all: I did consider taking a gap year from my PhD to do a one-year journalism fellowship, and I also applied to a summer internship that would’ve meant taking a two-month break from my research. In short, some exploration is possible, but much less than would be possible if you weren’t doing an MD/PhD.) Finally, an MD/PhD preserves very few options that wouldn’t be available if you “just” did an MD (or an MD and an MPH, etc.). An MD/PhD likely keeps some doors—particularly those in academic medicine—propped slightly further ajar, and so there may be this diffuse, vibe-y way in which it seems to confer flexibility and choice. But I suspect most successful MD/PhDs could have achieved similar careers with just an MD if they had prioritized acquiring research training by other means (e.g., during medical school or fellowship). The people for whom doing an MD/PhD does meaningfully preserve career options are people who would not have otherwise done medical training, since it’s impossible to practice medicine without an MD or DO. But if you’re considering spending at a minimum seven years completing clinical training (medical degree and residency) because you think you may want to practice medicine, I would strongly advise you to do much less costly things to resolve this uncertainty—shadow for many hours with many different kinds of clinicians, take a job in a clinical setting, talk to lots of doctors about their careers (including ones who have given up clinical practice), and so on. Reason #5: A couple of people whose careers you want to emulate did MD/PhDs Elaboration: Looking around the world and identifying people whose careers you’d want to have is a very natural way of picking a career. I suspect part of the reason we do this is because people ask us from an early age what we want to be when we grow up, and “who do I know who has a cool career” is understandably how we first learn to reason about this. Why I don’t endorse this reason: I think what matters is: what percent of people who did an MD/PhD have careers that you would want. You may be able to narrow the reference class further: for instance, I would consider what percent of social science MD/PhDs have careers I would want, rather than looking at MD/PhDs writ large. The reason I do not think you should try to emulate the careers of one or two people is that their experiences may not generalize. As just one example of this, shortly after I applied to MD/PhD programs, I heard Jim Kim—an MD/PhD, former director of the World Bank, and friend and colleague of Paul Farmer’s—give a talk where he explicitly advised the many pre-meds in the audience not to try to emulate Dr. Farmer’s career. His rationale (put more gently and eloquently) was something like: Paul Farmer was exceptional in a number of ways, and trying to emulate him is like watching Usain Bolt run a race and deciding to become an Olympic sprinter. I left the talk feeling a bit indignant, but now realize that Dr. Kim was right: the way Dr. Farmer approached his medical training—spending similar amounts of time in Haiti and Boston—is prohibited by most medical school curricula, and would be unfathomably hard to do. In short, Dr. Farmer was able to have his exceptional career because he had a specific combination of values and traits—alongside important contextual factors—that made it possible for him to do the things he did. This is not to say that you are not exceptional, but you likely have different values and traits—and are operating in a different context—than the person whose career you hope to emulate, and these things will make it impossible to chart their exact course. Given this, it makes more sense to consider the typical career that an MD/PhD in your field has. Assume you'd end up doing that. Would you be happy? If you would only be happy doing something that a small fraction of MD/PhDs do, I think it is worth seriously considering whether there are other (ideally more direct) paths towards doing that thing. Reason #6: It’s nice to have a clear, well-defined plan for how you’ll spend the next 7-10 years Elaboration: I don’t think this is explicitly surfaced as a reason for most people, but the prospect of being able to punt a lot of career and life decisions until you near the end of your training is reassuring for many. I think part of me had also assumed that by the time I was 30, I would have figured out how I wanted to spend my life, and I would then have the degrees I needed to do it. But for most people, career uncertainty (and the existential angst that accompanies this) is just a perennial feature of life for people who care a lot about their careers and have options. If anything, I’ve perhaps become more uncertain about what career I want to have, particularly as certain options have started to seem unrealistic, or misaligned with other things I care about (like not spending tons of time away from my partner). Why I don’t endorse this reason: First, if you are the kind of person who is inclined towards existential angst, and is drawn to MD/PhD training because you think it will exempt you from said angst, I promise you will find lots of other things to feel angsty about during your MD/PhD, like: What PhD should I do? What lab should I join? What medical specialty do I want to do? Do I even want to do a residency? How hard do I want to work? Should I marry this person? Do I want to stay in this city? Do I want to have kids? Will having kids now versus later be worse for my career? Moreover, you will likely feel angst about the paths that doing an MD/PhD has prevented you from taking. As you see your friends who didn’t do MD/PhDs move to different cities, get different degrees, change careers, make more money than you, and so on, a part of you may wonder: “What paths might I have pursued during my twenties had I not decided to do an MD/PhD?” In short, fretting about the roads taken and not taken is a (healthy in moderation) inevitability for many people, and doing an MD/PhD will not exempt you from this. Equally important, though, is the fact that your values are likely to shift during your twenties, and depending on how they shift, having a clear, well-defined plan for the next 7-10 years may cease to be a good thing. I had assumed by the time I graduated college, my values and goals would remain relatively stable for the rest of my life, since I attributed past shifts to the process of growing up. I did not anticipate that I would change about as much between the ages of 23 and 30 as I did between the ages of 16 and 23. I don’t think this is true for everyone, and if you’re the kind of person who has known for a long time (say, more than five years) that you want to do an MD/PhD, you may not need to worry as much about your values and goals shifting. But if you are someone who has repeatedly changed your mind about what to do with your life, and are drawn to an MD/PhD because you think it will provide you with some certainty and structure, I am inclined to think that this is actually a reason not to do an MD/PhD, since your priorities may continue to change, leaving you feeling constrained by the rigidity of a 7-10 year degree. What are good reasons to do a MD/PhD? I think a natural way to decide whether you want to do an MD/PhD is to think about this decision like the decision about whether to go down a particular water slide at a waterpark—primarily: “does that water slide look fun?” (i.e., the MD/PhD training) and less: “will it spit me out in a pool I want to be in?” (i.e., the remainder of your career). I do not, however, think this is the right way to think about whether to do an MD/PhD. Instead, I think it makes more sense to focus on the pool you want to end up in, and then work backwards: there may be multiple slides into that pool, a few ladders, and you could always just jump in off the edge. Which pool? I think MD/PhD training makes the most sense for people who want to end up in the academic medicine pool, and specifically, for those who want to spend the bulk of their time doing research, and a smaller percentage of time doing clinical medicine (i.e., somewhere between a 60/40 and 80/20 research/clinical split). I used to think MD/PhDs made sense for people with other career goals goals, but I’ve become increasingly skeptical that doing an MD/PhD is the best option for most people who don’t want to do academic medicine. The reason I think this is because for almost anything else you want to do in medicine (or research), there is probably a more direct path. If you want to spend most of your time practicing medicine, you may not need the PhD (especially given you’ll have lots of time to do research during your medical training—e.g., one year during medical school and two years during fellowship). If you want to spend less than 20% of your time practicing medicine—or are unsure whether you want to take care of patients at all—I don’t think it makes a ton of sense to spend seven years doing medical training (at least until you become more certain about wanting to practice medicine). I also think that if you’re someone who is on the fence about medicine (as opposed to the PhD), other, non-MD clinical degrees may be worth considering instead, since you may be able to acquire the clinical knowledge and skills you need in less time. Finally, people who want to pair clinical practice with something other than research (e.g., policy work, hospital administration, or consulting) should strongly consider degrees aside from a PhD (e.g., an MPH, MPP, MBA, or DrPH), since most PhD programs aim to train researchers, rather than practitioners, so may not leave you with the most relevant skillset. Which slide? My claim that you should pick an efficient path towards the pool that you want to end up in warrants defense, since someone could plausibly respond: “Why should I take the most direct path to the pool I want to end up in? MD/PhD training seems fun.” And I do think it is super important to choose a path that you’re viscerally excited about. Having taken three gap years myself, I also don’t want this advice to be misconstrued as “don’t explore options,” but rather: “all else equal, if there’s a less costly, more efficient path toward the same final professional destination, and that path seems fun too, choose the efficient path." Part of the reason I think you should consider other options rather than an MD/PhD if another path can get you to the same destination is that MD/PhDs are partly taxpayer funded—and MD/PhD spots are limited—so there’s an argument for not using limited public resources if you don’t need them. (And to be clear: if you need them, you should use them.) There are also other reasons to pursue a more efficient path: (1) training efficiently will likely benefit you financially, (2) ideally, it seems better—less stressful, more conducive to long-term success—to be more established in your career by the time you have kids, if you want kids (although I can't speak to this personally), and (3) people tend to have more impact as they become more established, so if this is something you care about, it’s better to train efficiently. Wanting to pursue a 70/30 career in academic medicine also does not necessarily mean you should do an MD/PhD the standard way (i.e., you go to college, potentially do a post-bac, do a 7-10 year MD/PhD, and then complete residency/fellowship). This is because there are multiple ways of attaining a career as a physician-researcher; for instance, you could take several research years rather than doing a PhD, or could do your clinical training first, and then do a PhD later (though this will tend to be costly). It’s worth flagging that this line of reasoning puts pressure on whether the standard MD/PhD path should be the standard physician-researcher path: if there are potentially less costly, more efficient ways of attaining the same career, why pursue 11+ years of post-university training (MD, PhD, residency)? My goal here is not to weigh in on the optimal way to train physician-researchers. But I would caution you against assuming that just because the path described above is the standard path, that means it is the right path for you (or even the right path for most people who want to become physician-researchers). For instance, I think there’s a strong argument for completing clinical training first, and then choosing a research career that maps onto your clinical interest (e.g., breast cancer research if you’re a breast oncologist) and clinical lifestyle (e.g., less time-sensitive projects if you’re often on call for your patients). Deferring your research training until you have a very clear sense of what research you want to do may also allow you to pursue the specific research skills you need, rather than investing a lot of time into cultivating ones you won’t use. For instance, my partner has an MD (and not a PhD), but is better at using statistics in his research—despite the fact that I have taken much more coursework in this—because he learned the specific skills he needed to do the projects he wanted to do. By contrast, I learned some general skills during the first two years of my PhD that wound up not translating that well to the research I did during the latter part. To summarize: If you don’t want to do academic medicine—and specifically a 60/40 to 80/20 research:clinical split—I think there are usually other training paths that make more sense. If you do want to do the 60/40 to 80/20 academic medicine thing, it’s worth considering whether there are non-MD/PhD paths to achieving the same goal, and systematically assessing the pros and cons of those options. If you want to spend most of your time doing research and some of your time practicing medicine, have systematically considered other paths, and think you’d really enjoy and benefit from MD/PhD training, I think it’s reasonable to do an MD/PhD. Next steps If you’re not sure whether to do an MD/PhD, here are some things I would consider doing:

Ultimately, these kinds of decisions are just really hard to make, and thinking about them a lot won’t always leave you sure of what to do. But thinking about these decisions systematically will tend to produce greater clarity, giving you more insight into your goals, values, motivations, things you want to avoid, and the relevant tradeoffs associated with different paths. Gaining clarity will help you make better decisions amidst uncertainty (and may help you grapple better with the uncertainty that remains). Good luck!

0 Comments

Many physicians worry that medical training is becoming too lax. Here’s a representative quote from NEJM’s Not Otherwise Specified podcast (which is insightful and worth listening to):

“10 years ago, students asked to have the day prior to their shelf exam off for clerkships, and they got it. And then, students asked that the day before that be a half day, and they got it. And then students asked, “What’s really the benefit of us having any overnight call on these clerkships?” And so, students went from having overnight calls on OB, internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry to only having one or two overnight calls their entire medical student career in the surgery clerkship… I think it’s that there is an awful lot of creep going on, and if you look at the differences from 10 years ago to now, or 5 years ago to now, they are pretty stark.” - Dr. Amy Holthouser In this blog post, I’ll aim to characterize and refute the view that medical trainees today aren't willing to work as hard as their predecessors. An acute on chronic problem Medical training has always been grueling, but many physicians believe it has gradually become less so. Historically, the expectation at many residency programs was that physicians would work 100-hour weeks for the duration of their residency training, often going 36 hours without sleeping. In 2003, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education implemented duty hour restrictions: residents could no longer work more than 80 hours per week or work more than 24 hours consecutively. In addition, residents were newly entitled to one day off per week. (Unfortunately, these changes didn’t clearly improve patient outcomes, and in some cases seemed to undermine them, although the evidence is difficult to parse, as it’s not clear these restrictions greatly reduced residents’ work hours.) In the years preceding COVID, more than half of medical students experienced burnout, while medical residents experienced depression at 3.5x the rate of the general population. Medical training programs thus began to take (seemingly effective) steps to improve trainee’s mental health by, for instance, making curricula pass-fail. Then COVID happened, compounding health workers’ rates of burnout, and accelerating many wellness-oriented changes in medical education (e.g., the addition of hybrid lectures and wellness days). Some of these changes were initiated by medical educators, but trainees have also begun to push for them, too; for instance, many residency programs have unionized, with residents seeking benefits like improved parental leave policies and call rooms without roaches. I think these changes have left many senior physicians with roughly the following perception: “When I trained, things were a lot harder. We worked constantly, never saw our families, and never slept. Trainees today have it much easier—in medical school, their courses and exams are pass-fail, and during residency, their time is more protected. These changes have also been accompanied by a cultural shift: trainees today feel more entitled to their relatively more comfortable lifestyles, and feel empowered to ask for even more benefits. Importantly, it’s not clear any of this is in the interest of patients, raising questions about whether trainees are forsaking their professional obligations. In addition, it’s not clear these changes are to the benefit of trainees, because part of what makes medicine rewarding and fun is accomplishing things that are harder than you ever thought possible, doing right by your patients, and becoming extremely competent and knowledgeable.” What this critique gets wrong Before getting into the substance of this critique, I want to first highlight that fretting about the youth’s declining work ethic is something of a right of passage for adults. That doesn’t make this critique wrong; tropes can be right, and it’s possible that people (and thus medical trainees) increasingly favor relaxation over rigor. But the fact that this narrative about medical trainees fits into a broader pattern of kids-these-days-ism—and is often supported more with vibes than data—means it warrants critical scrutiny. That said, I take seriously that a lot of people who have been in medicine longer than I have think two things are true: first, medical trainees today work less hard than their predecessors, and second, that trainees (wrongly) think that “being mentally healthy is equated with feeling good or calm or relaxed,” and thus are unwilling to experience what we might call “marathon joy” (i.e., the joy associated with accomplishing something truly difficult). The problem is that I think both critiques are empirically incorrect: I have yet to see much evidence that, over the course of their training, trainees work fewer hours than they used to, or that they insufficiently appreciate marathon joy. Indeed, I think there’s substantial evidence that by the time medical trainees finish their training, they will have worked longer and harder than their predecessors did:

In some ways, medical training has become easier than it was thirty years ago; for instance, residents no longer draw labs on their patients and call schedules have become less brutal. But there seems to be very little evidence that medical trainees today spend fewer total hours training, or find the average hour more educational, interesting, relaxing, or rewarding. And I think trainees—most of whom have spent their entire adolescence and adulthood working extremely hard—feel gaslit when they’re told, essentially: “you’re working less hard than your predecessors, so if you’re burnt out, you can’t blame your environment.” So where does this narrative come from? My guess is that things like wellness days, duty hour restrictions, and phlebotomists constitute clear, discrete examples of interventions that have made medical trainees’ lives easier. Meanwhile, things like gradually increasing hospital turnover, sicker patients, Step 2 score creep, and longer training paths have impacted trainees’ lives in significant, but subtler, ways, and are correspondingly overlooked. It’s not clear to me what we ought to do about this—how can we keep medical education rigorous without making trainees more burned out than they already are? But we need to correctly diagnose the problem in order to treat it, and when we conclude simply that trainees are unwilling to push themselves as hard, we miss an important piece of the puzzle: medical trainees today may not be running as fast, but they’re running a longer, steeper race. Where is it?

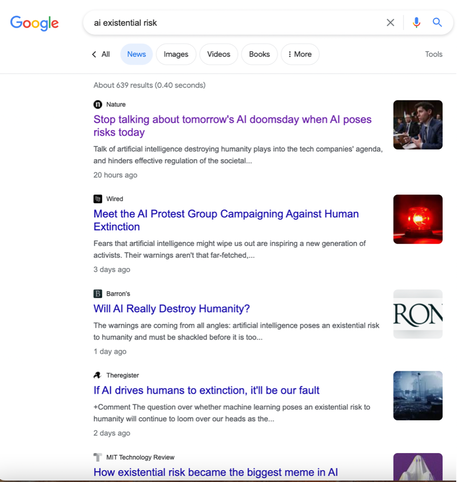

Biounethical.com, or search Bio(un)ethical on normal podcasting platforms. (Apple, Spotify, Google.) What is it? On each episode, we interview an expert on an important and controversial issue in bioethics. For instance, in our first few episodes, we consider the following questions: Should there be risk limits on research involving consenting participants? Does the IRB system do more harm than good? Should patients with intractable mental illness have access to medical aid in dying? What is the point of teaching ethics to professional school students? Who are we? I (Leah) am an MD/PhD candidate at Harvard Medical School and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Sophie is a PhD candidate in philosophy at MIT. Previously, we both spent two years as pre-doctoral fellows in the NIH Department of Bioethics. We have different academic backgrounds, different research interests, and different ethical commitments. Despite these differences, in our own conversations, we often wind up agreeing on how we should approach various bioethical issues. And when we continue to disagree, we are generally able to identify the specific sources of disagreement, while finding substantial common ground. We hope to do something similar on our podcast, and to thereby progress debates on controversial issues in bioethics. Who is the podcast for? We aim to have conversations at a high level and to meaningfully engage with the issues we discuss, which is why the episodes are ~90 minutes long. That said, we hope the podcast will be accessible to anyone interested in bioethical issues, including those without a background in any given subject area. To this end, we provide some context at the start of every episode and define concepts and terms as they arise. We think you might be especially interested in the podcast if you’re interested in bioethics, philosophy, or effective altruism. Why are we doing this? Generally speaking, we hope to improve discourse around bioethical issues in three ways. First, we are skeptical that certain norms in medicine, science, and public health are the right ones. We want to question them, and hopefully incite further discourse about them. Second, we aim to build bridges between different communities working independently on related issues. For instance, people in the bioethics community and people in the effective altruism community have researched and written extensively on human challenge trials, resource allocation, pandemic risk, and so on, but there has been relatively limited productive discourse between these communities. We hope the podcast will encourage members of different camps to talk to each other (by, for instance, showing that individuals in each share many of the same ethical commitments and empirical assumptions, even when they arrive at different conclusions about what policies we should implement or actions we should take). Meanwhile, many bioethicists believe philosophers have no meaningful role to play in contemporary bioethics, and many philosophers look down on bioethics as a sub-discipline that requires little philosophical skill. We hope the podcast will demonstrate that philosophy is vital to making progress in bioethics, and that bioethics involves more than the “simple” application of existing concepts and principles to real-world cases. Third, we want to make high-quality bioethics discourse more accessible to non-bioethicists. Currently, bioethics discourse exists in two main forms. First, bioethicists often give short quotes to journalists or write brief op-eds on hot-button issues. You can only say so much in a few hundred words, which makes it challenging to discuss bioethical issues in a nuanced way in this format. While important, this kind of black-and-white discussion of bioethical issues (“we shouldn’t do challenge trials because they’re too risky”), can contribute to polarization. Second, bioethicists often convey the deeper versions of their ideas in lengthy journal articles. But non-bioethicists may not have access, the desire, or the time to read thousands of words on a narrow bioethical issue. And we don’t think someone should have to delve deeply into the bioethics literature to understand a bioethicist’s perspective on an issue, or what the bioethics community thinks about it. We thus hope to create a discourse that occurs at a “medium” depth (deeper than a newspaper article, but shallower than a journal article) for people who are thinking seriously about bioethical issues, but want to engage with them more casually. Logistical stuff In Season 1, we will release episodes every other Tuesday for ten weeks, between August and December. You can sign up for our mailing list to be notified when new episodes are released, or you can follow us on Twitter (leah_pierson and sophiehgibert). Our podcast is supported by a grant from Amplify Creative Grants. Final thoughts There’s a learning curve associated with figuring out how to do a podcast well, so you’ll hear us learn and grow as hosts as the episodes progress That said, we’d be eager to hear your feedback and suggestions (including for topics and guests), which you can submit at biounethical.com. Please also rate and review the podcast on normal podcasting platforms. Thanks in advance for your support. We look forward to sharing these conversations with you. There is a new editorial in Nature arguing that discussions pertaining to risks posed by AI—including biased decision-making, the elimination of jobs, autocratic states’ use of facial recognition, and algorithmic bias in how social goods are distributed—are “being starved of oxygen” by debates about AI existential risk. Specifically, the authors assert that: “like a magician’s sleight of hand, [attention to AI x-risk] draws attention away from the real issue.” The authors encourage us to "stop talking about tomorrow's AI doomsday when AI poses risks today."

People have been making this claim a lot, and while different versions have been put forward, the general take seems to be something like:

Versions of this claim rely on the assumption that there is a specific kind of relationship between discussions about AI x-risks and other AI risks, namely: A parasitic relationship: Discussing AI x-risk causes us to discuss other AI risks less. However, the relationship could instead be: A mutual relationship: Discussing AI x-risk causes us to discuss other AI risks more. Or: A commensal relationship: Discussing AI x-risk doesn't cause us to discuss other AI risks less or more. It’s not clear that we generally starve issues of oxygen by discussing related ones: for instance, the Nature editorial does not suggest that discussions about privacy risks come at the expense of discussions about misinformation risks. And there are reasons to think there could be a mutual relationship between discussions about different kinds of AI risks. Some of the risks posed by AI that are discussed in the Nature editorial may lie on the pathway to AI x-risk. Talking about AI x-risk may help direct attention and resources to mitigating present risks, and addressing certain present risks may help mitigate x-risks. Indeed, there are significant overlaps in the regulatory solutions to these issues: that is why Bruce and I suggest that we should discuss and address the existing and emerging risks posed by misaligned AI in tandem. There are also reasons to think that the relationship between discussions of AI x-risk and other risks could be commensal. Public discourse is messy and complicated. It isn’t a limited resource in the way that kidneys or taxpayer dollars are. Writing a blog post about AI x-risk doesn’t lead to one fewer blog posts about other AI risks. While discourse is partly comprised of limited resources (e.g., article space in a print newspaper), even here, there may not be direct tradeoffs between discussions of AI x-risk and discussions of other AI risks. Indeed, many of the articles I have read about AI x-risk also discuss other risks posed by AI. To assess this, I did a quick Google search for “AI existential risk” and reviewed the first five articles that came up under “News,” all of which mention risks that are not existential risks—those described above in Nature, algorithmic bias in Wired, weapons that are “not an existential threat” in Barron’s, mass unemployment in the Register, and discriminatory hiring and misinformation in MIT Tech Review (see screenshot below). So even if it is the case that newspapers are devoting more article space to AI x-risk, and this leaves less article space for everything else, it’s not clear that this leads to fewer words being written about other AI risks. My point is that we should not accept at face value the claim that discussing AI x-risk causes us to pay insufficient attention to other, extremely important risks related to AI. We should aim to resolve uncertainty about these (potential) tradeoffs with data—i.e., by tracking what articles have been published on each issue over time, looking at what articles are getting cited and shared, assessing what government bodies are debating and what policies they are issuing, and so on. Asserting that there are direct tradeoffs where there may not be risks undermining efforts to have productive discussions about the important, intersecting risks posed by AI. Medical students are socialized to feel like we don't understand clinical practice well enough to have strong opinions about it. This happens despite the wisdom, thoughtfulness, and good intentions of medical educators; it happens because of basic features of medical education. First, the structure of medical school makes medical students feel younger—and correspondingly less competent, reasonable, and mature—than we are. Two-thirds of medical students take gap years between college and medical school, so many of us go from living in apartments to living in dorms; from working full-time jobs to attending mandatory 8am lectures; from freely scheduling doctors' appointments to being unable to make plans because we haven't received our schedules. I once found myself moving into a new apartment at 11pm because my lease ended that day, but I had been denied permission to leave class early. Professionalism assessments also play a role. "Professionalism" is not well defined, and as a result, "behaving professionally" has more or less come to mean "adhering to the norms of the medical profession," or even just "adhering to the norms the people evaluating you have decided to enforce." These include ethical norms, behavioral norms, etiquette norms, and any other norms you might imagine. For instance, a few months into medical school, my class received this email: "Moving the bedframes violates the lease agreement that you signed upon entering [your dorm]. You may have heard a rumor from more senior students that this is an acceptable practice. Unfortunately, it is not... If you have moved or accepted a bed, and we do not hear from you it will be seen as a professionalism issue and be referred to the appropriate body." (emphasis added) When someone tells you early in your training that something is a professionalism issue, your reaction may be "hm, I don't really see why moving beds is an issue that's relevant to the medical profession, but maybe I'll come to understand." First-year medical students are inclined to be deferential because we recognize how little we know about the medical profession. We do not understand the logic behind, for instance, rounds, patient presentations, and 28-hour shifts. Many of these norms eventually start to make sense. I've gone from wondering why preceptors harped so emphatically on being able to describe a patient in a single sentence to appreciating the efficiency and clarity of a perfect one-liner. But plenty of norms in medicine are just bad. Some practices are manifestations of paternalism (e.g., answering patients' questions in a vague, non-committal way), racism or sexism (e.g., undertreating Black patients' pain), antiquated traditions (e.g., wearing coats that may transmit disease), or the brokenness of the US health care system (e.g., not telling patients the cost of their care). The bad practices are often subtle, and even when they aren't, it can take a long time to realize they aren't justifiable. It took me seeing multiple women faint from pain during gynecologic procedures before I felt confident enough to tentatively suggest that we do things differently. My default stance was "there must be some reason they're doing things this way," and it required an overwhelming amount of evidence to change my mind.

Other professions undoubtedly have a similar problem: new professionals in any field may not feel that they can question established professional norms until they've been around long enough that the norms have become, well, normalized. As a result, it may often be outsiders who push for change. For instance, it was initially parents—not teachers—who lobbied for the abolition of corporal punishment in schools. Similarly, advocacy groups have created helplines to support patients appealing surprise medical bills, even as hospitals have illegally kept prices opaque. The challenge for actors outside of medicine, though, is that medicine is a complicated and technical field, and it is hard to challenge norms that you do not fully understand. Before I was a medical student, I had a doctor who repeatedly "examined" my injured ankle over my shoe. I didn't realize until my first year of medical school that you can't reliably examine an ankle this way. In some ways, medical students are uniquely well-positioned to form opinions about which practices are good and bad. This is because we are both insiders and outsiders. We have some understanding of how medicine works, but haven't yet internalized all of its norms. We're expected to learn, so can ask "Why is this done that way?" and evaluate the rationale. And we rotate through different specialties, so can compare across them, assessing which practices are pervasive and which are specific to a given context. Our insider/outsider status could be both a weakness and a strength: we may not know medicine, but our time spent working outside of medicine has left us with other knowledge; we may not understand clinical practice yet, but we haven't been numbed to it, either. One of the hardest things medical students have to do is remain open and humble enough to recognize that many practices will one day make sense, while remaining clear-eyed and critical about those that won't. But the concept of professionalism blurs our vision. It gives us a strong incentive not to form our own opinions because we are being graded on how well we emulate norms. Assuming there are good reasons for these norms resolves cognitive dissonance, while asking hard questions about them risks calling other doctors' professionalism into question. Thus, professionalism makes us less likely to trust our opinions about the behaviors we witness in the following way. First, professionalism is defined so broadly that norms only weakly tied to medicine fall under its purview. Second, we know we do not understand the rationales underlying many professional norms, so are inclined to defer to more senior clinicians about them. In combination, we are set up to place little stock in the opinions we form about the things we observe in clinical settings, including those we're well-positioned to form opinions about. In the absence of criticism and pushback, entrenched norms are liable to remain entrenched. This piece was originally published on Bill of Health, the blog of Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

There has been too little evaluation of ethics courses in medical education in part because there is not consensus on what these courses should be trying to achieve. Recently, I argued that medical school ethics courses should help trainees to make more ethical decisions. I also reviewed evidence suggesting that we do not know whether these courses improve decision making in clinical practice. Here, I consider ways to assess the impact of ethics education on real-world decision making and the implications these assessments might have for ethics education. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) includes “adherence to ethical principles” among the “clinical activities that residents are expected to perform on day one of residency.” Notably, the AAMC does not say graduates should merely understand ethical principles; rather, they should be able to abide by them. This means that if ethics classes impart knowledge and skills — say, an understanding of ethical principles or improved moral reasoning — but don’t prepare trainees to behave ethically in practice, they have failed to accomplish their overriding objective. Indeed, a 2022 review on the impact of ethics education concludes that there is a “moral obligation” to show that ethics curricula affect clinical practice. Unfortunately, we have little sense of whether ethics courses improve physicians’ ethical decision-making in practice. Ideally, assessments of ethics curricula should focus on outcomes that are clinically relevant, ethically important, and measurable. Identifying such outcomes is hard, primarily because many of the goals of ethics curricula cannot be easily measured. For instance, ethics curricula may improve ethical decision-making by increasing clinicians’ awareness of the ethical issues they encounter, enabling them to either directly address these dilemmas or seek help. Unfortunately, this skill cannot be readily assessed in clinical settings. But other real-world outcomes are more measurable. Consider the following example: Physicians regularly make decisions about which patients have decision-making capacity (“capacity”). This determination matters both clinically and ethically, as it establishes whether patients can make medical decisions for themselves. (Notably, capacity is not a binary: patients can retain capacity to make some decisions but not others, or can retain capacity to make decisions with the support of a surrogate.) Incorrectly determining that a patient has or lacks capacity can strip them of fundamental rights or put them at risk of receiving care they do not want. It is thus important that clinicians correctly determine which patients possess capacity and which do not. However, although a large percentage of hospitalized patients lack capacity, physicians often do not feel confident in their ability to assess capacity, fail to recognize that most patients who do not have capacity lack it, and often disagree on which patients have capacity. Finally, although capacity is challenging to assess, there are relatively clear and widely agreed upon criteria for assessing it, and evaluation tools with high interrater reliability. Given this, it would be both possible and worthwhile to determine whether medical trainees’ ability to assess capacity in clinical settings is enhanced by ethics education. Here are two potential approaches to evaluating this: first, medical students might perform observed capacity assessments on their psychiatry rotations, just as they perform observed neurological exams on their neurology rotations. Students’ capacity assessments could be compared to a “gold standard,” or the assessments of physicians who have substantial training and experience in evaluating capacity using structured interviewing tools. Second, residents who consult psychiatry for capacity assessments could be asked to first determine whether they think a patient has capacity and why. This determination could be compared with the psychiatrist’s subsequent assessment. Programs could then randomize trainees to ethics training — or to a given type of ethics training — to determine the effect of ethics education on the quality and accuracy of trainees’ capacity assessments. Of course, ethics curricula should do much more than make trainees good at assessing capacity. But measuring one clinically and ethically significant endpoint could provide insight into other aspects of ethics education in two important ways. First, if researchers were to determine that trainees do a poor job of assessing capacity because they have too little time, or cannot remember the right questions to ask, or fail to check capacity in the first place, this would point to different solutions — some of which education could help with, and others of which it likely would not. Second, if researchers were to determine that trainees generally do a poor job of assessing capacity because of a given barrier, this could have implications for other kinds of ethical decisions. For instance, if researchers were to find that trainees fail to perform thorough capacity assessments primarily because of time constraints, other ethical decisions would likely be impacted as well. Moreover, this insight could be used to improve ethics curricula. After all, ethics classes should teach clinicians how to respond to the challenges they most often face. Not all (or perhaps even most) aspects of clinicians’ ethical decision-making are amenable to these kinds of evaluations in clinical settings, meaning other types of evaluations will play an important role as well. But many routine practices — assessing capacity, acquiring informed consent, advance care planning, and allocating resources, for instance — are. And given the importance of these endpoints, it is worth determining whether ethics education improves clinicians’ decision making across these domains. This piece was originally published on Bill of Health, the blog of Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

Medical students spend a lot of time learning about conditions they will likely never treat. This weak relationship between what students are taught and what they will treat has negative implications for patient care. Recently, I looked into discrepancies between U.S. disease burden in 2016 and how often conditions are mentioned in the 2020 edition of First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, an 832 page book sometimes referred to as the medical student’s bible. The content of First Aid provides insight into the material emphasized on Step 1 — the first licensing exam medical students take, and one that is famous for testing doctors on Googleable minutia. This test shapes medical curricula and students’ independent studying efforts — before Step 1 became pass-fail, students would typically study for it for 70 hours a week for seven weeks, in addition to all the time they spent studying before this dedicated period. My review identified broad discrepancies between disease burden and the relative frequency with which conditions were mentioned in First Aid. For example, pheochromocytoma, a rare tumor that occurs in about one out of every 150,000 people per year — is mentioned 16 times in First Aid. By contrast, low back pain — the fifth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years, or DALYs, in the U.S., and a condition that has affected one in four Americans in the last three months — is mentioned only nine times. (Disease burden is commonly measured in DALYs, which combine morbidity and mortality into one metric. The leading causes of DALYs in the U.S. include major contributors to mortality, like ischemic heart disease and lung cancer, as well as major causes of morbidity, like low back pain.) Similarly, neck pain, which is the eleventh leading cause of DALYs, is mentioned just twice. Both neck and back pain are also often mentioned as symptoms of other conditions (e.g., multiple sclerosis and prostatitis), rather than as issues in and of themselves. Opioid use disorder, the seventh leading cause of DALYs in 2016 and a condition that killed more than 75,000 Americans last year, is mentioned only three times. Motor vehicle accidents are mentioned only four times, despite being the fifteenth leading cause of DALYs. There are some good reasons why Step 1 content is not closely tied to disease burden. The purpose of the exam is to assess students’ understanding and application of basic science principles to clinical practice. This means that several public health problems that cause significant disease burden — like motor vehicle accidents or gun violence — are barely tested. But it is not clear Step 2, an exam meant to “emphasize health promotion and disease prevention,” does much better. Indeed, in First Aid for the USMLE Step 2, back pain again is mentioned fewer times than pheochromocytoma. Similarly, despite dietary risks posing the greatest health threat to Americans (including smoking), First Aid for the USMLE Step 2 says next to nothing about how to reduce these risks. More broadly, there may also be good reasons why medical curricula should not perfectly align with disease burden. First, more time should be devoted to topics that are challenging to understand or that teach broader physiologic lessons. Just as researchers can gain insights about common diseases by studying rare ones, students can learn broader lessons by studying diseases that cause relatively little disease burden. Second, after students begin their clinical training, their educations will be more closely tied to disease burden. When completing a primary care rotation, students will meet plenty of patients with back and neck pain. But the reasons some diseases are emphasized and taught about more than others often may be indefensible. Medical curricula seem to be greatly influenced by how well understood different conditions are, meaning curricula can wind up reflecting research funding disparities. For instance, although eating disorders cause substantial morbidity and mortality, research into them has been underfunded. As a result, no highly effective treatments targeting anorexia or bulimia nervosa have emerged, and remission rates are relatively low. Medical schools may not want to emphasize the limitations of medicine or devote resources to teaching about conditions that are multifactorial and resist neat packaging, meaning these disorders are often barely mentioned. But, although eating disorders are not well understood, thousands of papers have been written about them, meaning devoting a few hours to teaching medical students about them would still barely scratch the surface. And even when a condition is understudied or not well understood, it is worth explaining why. For instance, if heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is discussed more than heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, students may wrongly conclude this has to do with the relative seriousness of these conditions, rather than with the inherent challenge of conducting clinical trials with the latter population (because their condition is less amenable to objective inclusion criteria). Other reasons for curricular disparities may be even more insidious: for instance, the lack of attention to certain diseases may reflect the medical community’s perceived importance of these conditions, or whether they tend to affect more empowered or marginalized populations. The weak link between medical training and disease burden matters: if medical students are not taught about certain conditions, they will be less equipped to treat these conditions. They may also be less inclined to specialize in treating them or to conduct research on them. Thus, although students will encounter patients with back pain or who face dietary risks, if they and the physicians supervising them have not been taught much about caring for these patients, these patients likely will not receive optimal treatment. And indeed, there is substantial evidence that physicians feel poorly prepared to counsel patients on nutrition, despite this being one of the most common topics patients inquire about. If the lack of curricular attention reflects research and health disparities, failing to emphasize certain conditions may also compound these disparities. Addressing this problem requires understanding it. Researchers could start by assessing the link between disease burden and Step exam questions, curricular time, and other resources medical students rely on (like the UWorld Step exam question banks). Organizations that influence medical curricula — like the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Liaison Committee on Medical Education—should do the same. Medical schools should also incorporate outside resources to cover topics their curricula do not explore in depth, as several medical schools have done with nutrition education. But continuing to ignore the relationship between disease burden and curricular time does a disservice to medical students and to the patients they will one day care for. This piece was originally published on Bill of Health, the blog of Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

I recently argued that we need to evaluate medical school ethics curricula. Here, I explore how ethics courses became a key component of medical education and what we do know about them. Although ethics had been a recognized component of medical practice since Hippocrates’ time, ethics education is a more recent innovation. In the 1970s, the medical community was shaken by several high-profile lawsuits alleging unethical behavior by physicians. As medical care advanced — and categories like “brain death” emerged — doctors found themselves facing challenging new dilemmas and old ones more often. In response to this, in 1977, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine became the first medical school to incorporate ethics education into its curriculum. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, medical schools increasingly began to incorporate ethics education into their curricula. By 2002, approximately 79 percent of U.S. medical schools offered a formal ethics course. Today, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) includes “adherence to ethical principles” among the competencies required of medical school graduates. As a result, all U.S. medical schools — and many medical schools around the world — require ethics training. There is some consensus on the content ethics courses should cover. The AAMC requires medical school graduates to “demonstrate a commitment to ethical principles pertaining to provision or withholding of care, confidentiality, informed consent.” Correspondingly, most medical school ethics courses review issues related to consent, end-of-life care, and confidentiality. But beyond this, the scope of these courses varies immensely (in part because many combine teaching in ethics and professionalism, and there is little consensus on what “professionalism” means). The format and design of medical school ethics courses also varies. A wide array of pedagogical approaches are employed: most rely on some combination of lectures, case-based learning, and small group discussions. But others employ readings, debates, or simulations with standardized patients. These courses also receive differing degrees of emphasis within medical curricula, with some schools spending less than a dozen hours on ethics education and others spending hundreds. (Notably, much of the research on the state of ethics education in U.S. medical schools is nearly twenty years old, though there is little reason to suspect that ethics education has converged during that time, given that medical curricula have in many ways become more diverse.) Finally, what can seem like consensus in approaches to ethics education can mask underlying differences. For instance, although many medical schools describe their ethics courses as “integrated,” schools mean different things by this (e.g., in some cases “integrated” means “interdisciplinary,” and in other cases it means “incorporated into other parts of the curriculum”). A study from this year reviewed evidence on interventions aimed at improving ethical decision-making in clinical practice. The authors identified eight studies of medical students. Of these, five used written tools to evaluate students’ ethical reasoning and decision-making, while three assessed students’ interactions with standardized patients or used objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs). Three of these eight studies assessed U.S. students, the most recent of which was published in 1998. These studies found mixed results. One study found that an ethics course led recipients to engage in more thorough — but not necessarily better — reasoning, while another found that evaluators disagreed so often that it was nearly impossible to achieve consensus about students’ performances. The authors of a 2017 review assessing the effectiveness of ethics education note that it is hard to draw conclusions from the existing data, describing the studies as “vastly heterogeneous,” and bearing “a definite lack of consistency in teaching methods and curriculum,” The authors conclude, “With such an array, the true effectiveness of these methods of ethics teaching cannot currently be well assessed especially with a lack of replication studies.” The literature on ethics education thus has several gaps. First, many of the studies assessing ethics education in the U.S. are decades old. This matters because medical education has changed significantly during the 21st century. (For instance, many medical schools have substantially restructured their curricula and many students do not regularly attend class in person.) These changes may have implications for the efficacy of ethics curricula. Second, there are very few head-to-head comparisons of ethics education interventions. This is notable because ethics curricula are diverse. Finally, and most importantly, there is almost no evidence that these curricula lead to better decision-making in clinical settings — where it matters. A slightly longer version of this piece was originally published on Bill of Health, the blog of Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

Recently, Derek Thompson pointed out in the Atlantic that the U.S. has adopted myriad policies that limit the supply of doctors despite the fact that there aren’t enough. And the maldistribution of physicians — with far too few pursuing primary care or working in rural areas — is arguably an even bigger problem. The American Medical Association (AMA) bears substantial responsibility for the policies that led to physician shortages. Twenty years ago, the AMA lobbied for reducing the number of medical schools, capping federal funding for residencies, and cutting a quarter of all residency positions. Promoting these policies was a mistake, but an understandable one: the AMA believed an influential report that warned of an impending physician surplus. To its credit, in recent years, the AMA has largely reversed course. For instance, in 2019, the AMA urged Congress to remove the very caps on Medicare-funded residency slots it helped create. But the AMA has held out in one important respect. It continues to lobby intensely against allowing other clinicians to perform tasks traditionally performed by physicians, commonly called “scope of practice” laws. Indeed, in 2020 and 2021, the AMA touted more advocacy efforts related to scope of practice that it did for any other issue — including COVID-19. The AMA’s stated justification for its aggressive scope of practice lobbying is, roughly, that allowing patients to be cared for by providers with less than a decade of training compromises patient safety and increases health care costs. But while it may be reasonable for the AMA to lobby against some legislation expanding the scope of non-physicians, the AMA is currently playing whack-a-mole with these laws, fighting them as they come up, indiscriminately. This general approach isn’t well supported by data — the removal of scope-of-practice restrictions has not been linked to worse care — and undermines the AMA’s credibility. The AMA’s own scope of practice website hardly bolsters its case. Under a heading that states “scope expansion does not equal expanding access to care,” the AMA claims only that “nonphysician providers (such as [nurse practitioners]) are more likely to practice in the same geographic locations as physicians” and “despite the rising number of [nurse practitioners] across the country, health care shortages still persist.” But unsurprisingly, both physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) are more likely to be found in geographic locations with more people, although NPs do represent a larger share of the primary care workforce in rural areas. The AMA’s scope of practice lobbying is particularly frustrating because the Association could improve both the supply and allocation of physicians in a more evidence-based way: by reforming U.S. medical education. In other countries, physicians receive fewer years of training but provide comparable care. Instead of insisting that NPs and other clinicians get more training, the AMA should be working to make U.S. medical education more efficient by pushing for the creation of more three-year medical degrees, more combined undergraduate and medical school programs, and shorter pathways into highly needed specialties. The AMA could also make careers in primary care and rural areas more accessible by lobbying for more loan forgiveness programs, scholarships, and training opportunities for medical students interested in these paths. Now is a pivotal time for the AMA to reconsider its aggressive scope of practice lobbying. Temporary regulations allowing NPs and other clinicians to do more during the COVID-19 pandemic could be evaluated and, if safe and cost-effective, expanded. At a time when the health care workforce is facing an unprecedented crisis, the AMA should fully atone for the workforce shortages it helped create. This piece was originally published on Bill of Health, the blog of Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

Academia often treats all areas of research as important, and two projects that will publish equally well as equally worthy of exploring. I believe this is misguided. Instead, we should strive to create an academic culture where researchers consider and discuss a project’s likely impact on the world when deciding what to work on. Though this view is at odds with current norms in academia, there are four reasons why a project’s potential to improve the world should be an explicit consideration. First, research projects can have massively different impacts, ranging from altering the course of human history to collecting dust. To the extent that we can do work that does more to improve people’s lives without imposing major burdens on ourselves, we should. Second, the choice of a research project affects a researcher’s career trajectory, and as some have argued, deciding how to spend one’s career is the most important ethical decision many will ever make. Third, most academic researchers are supported by public research dollars or work at tax exempt institutions. To the extent that researchers are benefitting from public resources, they have an obligation to use research resources in socially valuable ways. Fourth, most researchers come from advantaged backgrounds. If researchers pick projects primarily based on their own interests, the research agenda will provide too few benefits to populations underrepresented in academia. One might push back on this view by arguing that the research enterprise functions as an effective market. Perhaps academic researchers already have strong incentives to choose projects that do more to improve the world, given these projects will yield more funding, publications, and job opportunities. On this view, researchers have no reason to consider a project’s likely positive impact; journal editors, grant reviewers, and hiring committees will do this for them. But the academic marketplace is riddled with market failures: some diseases receive far more research funding than other, comparably severe ones; negative findings and replication studies are less likely to get published; research funders don’t always consider the magnitude of a problem in deciding which grants to fund; and so on. And although these problems warrant structural solutions, individual researchers can also help mitigate their effects. One might also argue that pursuing a career in academia is hard enough even when you’re studying the thing you are most passionate about. (I did a year of Zoom PhD; you don’t have to convince me of this.) On this view, working on the project you’re most interested in should crowd out all other considerations. But while this may be the case for some people, this view doesn’t accord with most conversations I’ve had with fellow graduate students. Many students enter their PhDs unsure about what to work on, and wind up deciding between multiple research areas or projects. Given that most have only worked in a few research areas prior to embarking on a PhD, the advice “choose something you’re passionate about” often isn’t very useful. For many students, adding “choose a project that you think can do more to improve the world” to the list of criteria for selecting a research topic would represent a helpful boundary, rather than an oppressive constraint. Of course, people will have different understandings of what constitutes an impactful project. Some may aim to address certain inequities; others may want to help as many people as possible. People also will disagree about which projects matter most even according to the same metrics: a decade ago, many scientists thought developing an mRNA vaccine platform was a good idea, but not one of the most important projects of our time. But the inherent uncertainty about which research is more impactful does not leave us completely in the dark: most would agree that curing a disease that kills millions is more important than curing a disease that causes mild symptoms in a few. In practice, identifying more beneficial research questions involves guessing at several hard to estimate parameters—e.g., How many people are affected by a given problem and how badly? Are there already enough talented people working on this such that my contributions will be less important? And will the people who read my paper be able to do anything about this? The more basic the research, the harder these kinds of questions are to answer. My goal here, though, is not to provide practical advice. (Fortunately, groups like Effective Thesis do.) My point is that researchers should approach the question of how much a given project will improve the world with the same rigor they bring to the work of the project itself. Researchers do not need to arrive at the best or most precise answer every time: over the course of their careers, seriously considering which projects are more important and, to some extent, picking projects on this basis will produce a body of work that does more good. |

Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

Posts

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed